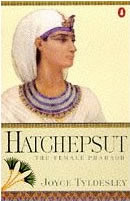

One of the most intriguing figures in Egyptian history is Hatchepsut[1], a woman who became pharaoh during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Too little material has survived the three and a half millennia that separate us from Hatchepsut to allow the writing of a conventional biography. We have, for example, no diaries, no letters, and not even palace archives from which to discern clues to her personality. Nevertheless, in her Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Joyce Tyldesley has written as full a biography as the extant evidence allows, and has managed to paint an engaging portrait of her life and times.

Hatchepsut was born a princess of the Tuthmosid royal house towards the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty. This was an age of warrior pharaohs. At the time of Hatchepsut’s birth, around a century had elapsed since the kings of Thebes, the great religious and political centre in Upper Egypt, had expelled the foreign Hyksos kings from Lower Egypt and reunified the Egyptian state. The pharaohs Ahmose I, Amenhotep I and Thutmose I, Hatchepsut’s father, had then pushed the borders of Egypt far north into Asia and south into Nubia. The empire they founded, the New Kingdom, would endure for five centuries and be seen, both then and later, as one of the glorious peaks of Egyptian civilisation. On the death of Tuthmose I, Hatchepsut’s half-brother and husband became the pharaoh Tuthmose II and she became queen of Egypt. Tuthmose II seems to have been quite a weak man and may well have been dominated by his sister-wife (the political history of the New Kingdom was full of strong-willed women as well as warrior pharaohs), but the despite this Hatchepsut was portrayed as an exemplary wife and queen. So far, so conventional. Tuthmose II died young and Hatchepsut soon found herself regent for the child Tuthmose III, a son of Tuthmose II by a secondary wife. This too was far from unusual - there had already been two very successful queen regents in the Eighteenth Dynasty - but it provided the opportunity that Hatchepsut’s extraordinary ambition needed.

By the seventh year of the regency, this ambition had fully flowered and the young Tuthmose had been pushed into the background. Egypt had seen queens regent and a queen regnant - Sobekneferu, last monarch of the Twelfth Dynasty - before but Hatchepsut then went one step further and assumed the titulary and powers of a pharaoh. This was a development of quite astonishing audacity - the pharaoh was not merely the ruler of Egypt but an incarnation of the god Horus and so a being who existed on a higher level than the rest of humanity - and it says something for Hatchepsut’s strength of personality and political skills that she managed this transformation seemingly without serious opposition and held onto power for two decades. She certainly maintained the loyalty of key members of her father’s and brother’s regime throughout her rule. Foremost amongst these was the steward Senenmut, who probably entered the royal service under Tuthmose II and became the most powerful figure in Hatchepsut’s regime. Tyldesley devotes a whole chapter to the career of Senenmut and his enigmatic relationship to the pharaoh.

The throne name chosen by Hatchepsut, Maatkare (“Maat is the soul of Re”), provides one clue to her political strategy. The concept of maat, which is often translated as “truth”[2] but means something closer to “correct-orderedness”, was a central one to the ancient Egyptians. Pharaohs and everyone else were supposed to act in conformance to this timeless correct way of organising the affairs of Egypt. The surviving monuments of Hatchepsut, including her sublime mortuary temple Djeser-Djeseru (“Holiest of the Holy”) at Deir el-Bahri, are “propaganda in stone” emphatically presenting the vision of Hatchepsut as the ideal pharaoh. So far as we can tell Hatchepsut’s reign was as stunningly successful as that of most of the other Tuthmosid pharaohs. (To some it has seemed disappointingly lacking in military glory - as was that of Tuthmose II - but it made up for this through a spectacular expedition to the exotic land of Punt in eastern Africa.)

Tyldesley also tells the story of the modern rediscovery of Hatchepsut and the varying attitudes of Egyptologists towards her. Until comparatively recently the most popular interpretation of Hatchepsut’s career revolved around a power struggle at the heart of the Tuthmosid family. Hatchepsut was supposedly an “evil stepmother” who usurped Tuthmose III’s rightful place for two decades and whose monuments were systematically defaced by Tuthmose is a fit of righteous anger when he became pharaoh. The book demolishes this interpretation quite thoroughly. Hatchepsut would clearly have had many opportunities to quietly dispose of the young Tuthmose III but failed to take advantage of any of them. Indeed, she even allowed him to lead important military expeditions, a development that would have been recklessly dangerous and entirely out of character if she hadn’t entirely trusted him. Nor is it easy to paint the young Tuthmose as a weakling dominated by his older relative, as he went on to become one of Egypt’s greatest conquerors. He must surely have seen her as a respected elder rather than the target of brooding resentment. Against this, however, must be weighed Tuthmose III’s attempts to erase the reign of Hatchepsut from history through a campaign of extensive (although incomplete) vandalisation and destruction of her monuments. However, the evidence suggests that this occurred late in his reign and Tyldesley interprets it as targeted not at Hatchepsut herself but at younger royal women who might try to emulate her and further complicate dynastic succession. She points out the significant fact that it was only representations of Hatchepsut as king that were destroyed, not those of her as queen consort.

Hatchepsut is a book that I thoroughly enjoyed reading. As with Tyldesley’s other “New Kingdom biographies” (of Nefertiti and Ramesses (II, the Great) it’s pleasantly concise, conveys a surprisingly vivid sense of its subjects life and times, and it taught me a lot of new things about ancient Egypt. I hope she writes more such biographies.

[1] Or sometimes “Hatshepsut”.

[2] In a similar sense to the ancient Persian asha.

Leave a comment